- 1 min read

Updated: May 17, 2022

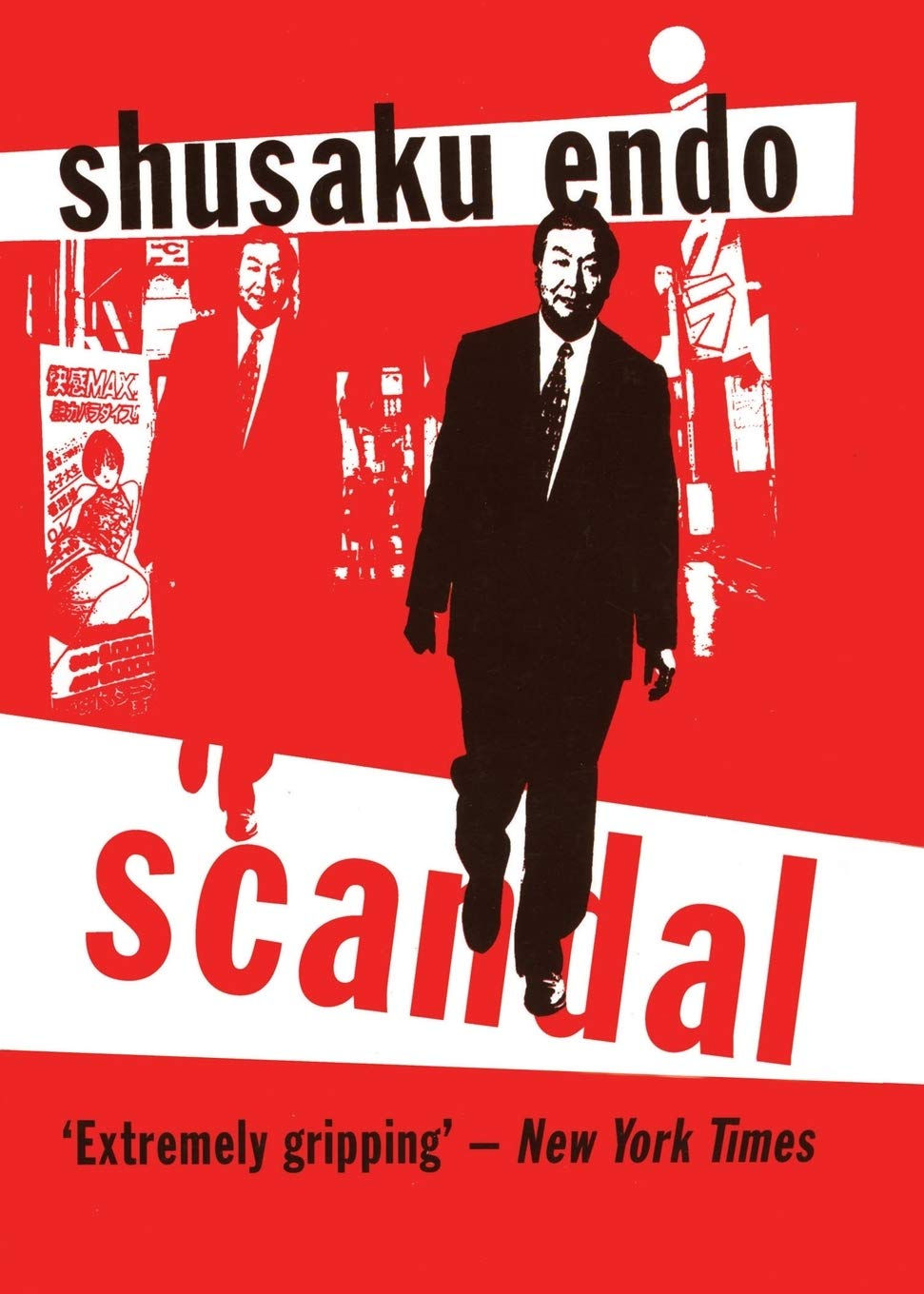

This 1986 novel by Shusaku Endo is a departure from a lot of his previous work, mainly historical fiction. Protagonist Suguro, a modern-day novelist similar in many respects to real-life Endo, receives an award for his writing at age 65. Leaving the ceremony he’s accosted by a drunken woman who blurts out that the revered Catholic author frequents a brothel in Shinjuku’s infamous Kabukicho district. Suguro, now convinced a doppelganger is out there bent on sullying his reputation, will seek out this double. Or is he actually him? Complicating the matter and stirring Suguro’s turmoil is a young girl he hires as an assistant and also a Madame Naruse, who volunteers as a nurse at a hospital for children by day, but by night is driven by a predilection for sadomasochism.

Although some parts didn’t cohere for me, I liked the story for its setting (Tokyo) and for how Endo maybe reveals aspects of his own character through the prose. But certain descriptions or words had me questioning the accuracy of the translation—I can’t put my finger on why I felt this exactly; they just didn’t seem like Endo’s. All in all, though, it’s a compelling read, and I’ve always been a sucker for doppelganger tales told to cast light on persona and bad behavior.